Late last legislative session, California lawmakers resuscitated a statute that had been dead for about 20 years. While the statute has been dormant, however, the area it dealt with is not: Bad faith and frivolous lawsuits.

Last fall, Assembly Bill 2494 reinstated Code of Civil Procedure § 128.5, with some amendments, effective January 1, 2015. If you have an older codebook, you’ll note the former version of the statute is still in there, but as subdivision (b)(1) stated, it pertained “only if the actions or tactics arise from a complaint filed, or a proceeding initiated, on or before December 31, 1994.”

Section 128.5 was put to rest in favor of CCP § 128.7, whose provisions are valid for actions filed on or after January 1, 1995. Section 128.7 remains in effect today.

What did former CCP § 128.5 do? What changed in 1994 to prompt the Legislature to create a different framework for sanctions? And why is 128.5 back again?

CCP § 128.5 was first added to the code in 1981. It was prompted by a 1978 case, Baugess v. Paine (22 Cal. 3d 626), which held that a trial court did not have inherent power to award attorneys’ fees as a sanction for the misbehavior of a party, and it could not do so absent statutory authority.

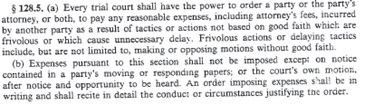

The first version of 128.5 was relatively short, and stated the following:

The section was amended a few times afterward. However, before the amendment we are concerned with — the 1994 amendment — something changed in the landscape of judicial sanctions.

That “something” was the 1993 amendment of Federal Civil Rules of Procedure Rule 11.

As the Federal Advisory Committee stated in its notes on the 1993 amendment:

This revision is intended to remedy problems that have arisen in the interpretation and application of the 1983 revision of the rule.

…

The rule retains the principle that attorneys and pro se litigants have an obligation to the court to refrain from conduct that frustrates the aims of Rule 1. The revision broadens the scope of this obligation, but places greater constraints on the imposition of sanctions and should reduce the number of motions for sanctions presented to the court. New subdivision (d) removes from the ambit of this rule all discovery requests, responses, objections, and motions subject to the provisions of Rule 26 through 37. …

In 1994, in addition to adding section 446 and repealing former section 447 of the Code of Civil Procedure, California Assembly Bill 3594 added section 128.7, added and repealed section 128.6 (which itself was later repealed in 2011), and limited 128.5 only to those actions or tactics arising on or before December 31, 1994. One bill analysis specifically noted that the measure replaced existing provisions with “a more stringent version based on federal law.”

(Note: The legislature continued to extend the sunset provision on section 128.7 until it deleted it altogether in 2006.)

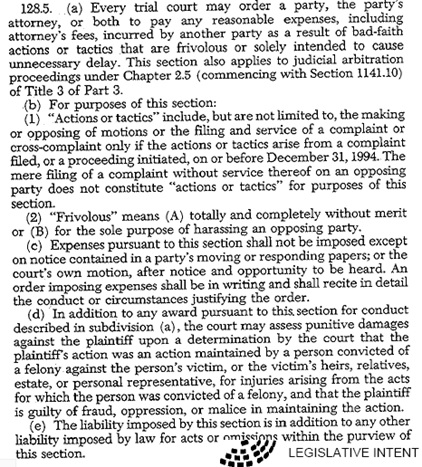

Section 128.7 limits sanctions to a “pleading, petition, written notice of motion, or other similar paper …” (Code Civ. Pro. § 128.7(b)) On the other hand, section 128.5 was not limited to pleadings – it applied to “bad-faith actions or tactics.” As noted in former 128.5, as amended in 1994:

And now we’re to the crux of the issue: why Section 128.5 has been brought back from the dead.

This is what AB 2494’s author, Assembly member Ken Cooley, had to say about that:

Unfortunately, bad-faith disobedience and tactics by either side are needlessly employed in litigation. It can result in clogging our courts and wasting precious judicial resources. Courts routinely give litigants the benefit of the doubt, but they have lost an important tool used to ensure bad faith actions that can materially harm the other party or the fairness of a trial are discouraged. Under existing law a court can compel obedience with a court order, but financially the most a court can do if a party violates one is find them in contempt with penalty of up to $1500. Moreover, if a case ends in a mistrial or in the release of protected documents it is difficult to undo the waste of judicial resources or harm done to the litigant who was not at fault.

It appears the Civil Justice Association of California was a sponsor of the 2014 legislation.

Today’s 128.5, as did its predecessor, applies to “bad-faith actions or tactics.” (Code Civ. Proc. § 128.5) However, in addition to other changes, today’s 128.5 contain provisions that refer to section 128.7, and is intended to be read in tandem with section 128.7. Further, subdivision (h) sets out reporting requirements to the California Research Bureau of the State Library, which is tasked with maintaining “a public record of information transmitted pursuant to this section for at least three years, or until this section is repealed, whichever occurs first …” (Code Civ. Proc. § 128.5(h))

Current 128.5 has a sunset clause of January 1, 2018, after which time it appears the 1994 version of 128.5 goes back into effect.